ARTISTS:

Teresa Busuttil

Inès Cook

Lily Trnovsky

Sian Watson

Chiranjika Grasby [curator]

In today’s society we’re faced with decreasing social bonds, a new yearning for intimacy, and a constant flood of bad news leaving us longing for safe places and salvation. This sentiment is reflected in today’s visual art, seeping into the minds of creatives. A contemporary reimagining of Romanticism – an artistic and intellectual movement commencing at the turn of the 19thC – is shining through as we are confronted with a revival of traditional work. Artists Teresa Busuttil, Inès Cook, Chiranjika Grasby, Sian Watson, and Lily Trnovsky have taken up the Romantic spirit. Yet, beyond the desire for the paradisiacal, beautiful, and magical, an eerie darkness is present. Through painting, video, and sculpture, the artists provide an insight into a Utopia doomed for failure.

The Romantic spirit invokes a subversive trend of reaching beyond limitations, manifesting itself in the form of unearthly counter-worlds and gloomy sketches. Symbolically charged landscapes and dream visions portray a deep skepticism about rigid conventions, and a call for artistic independence. Today’s generation of artists disrupt current social and political climates with aesthetics beyond the ordinary, forming a vocabulary of desire rooted in the historical Romantic movement.

Contemporary practice encompasses numerous variations of this theme, ranging from anamorphic creatures and their behaviours to an overwhelming blend between fantasy and reality. Sian Watson’s figures are just small fragments of an imagined ecosystem, posed and displayed like artefacts, they accumulate into herds and families or sit alone as surviving relics. Their coarse surfaces suggest a passing of time, and lift them into the visual language of archaeological discovery or historic idol. Watson’s works shift our known realities – they feel familiar at first glance, yet carry elements of the unknown. Much like the multimedia works of Teresa Busuttil, which mix fantasy with personal narrative and the lived experience of a multicultural upbringing. Common motifs throughout her works are the ocean and coastlines – seashells, waves, boats – a suggestion of journey with a gentle thread of melancholy. She tells stories through her practice, and we are given glimpses into postcard locations we’ll never visit.

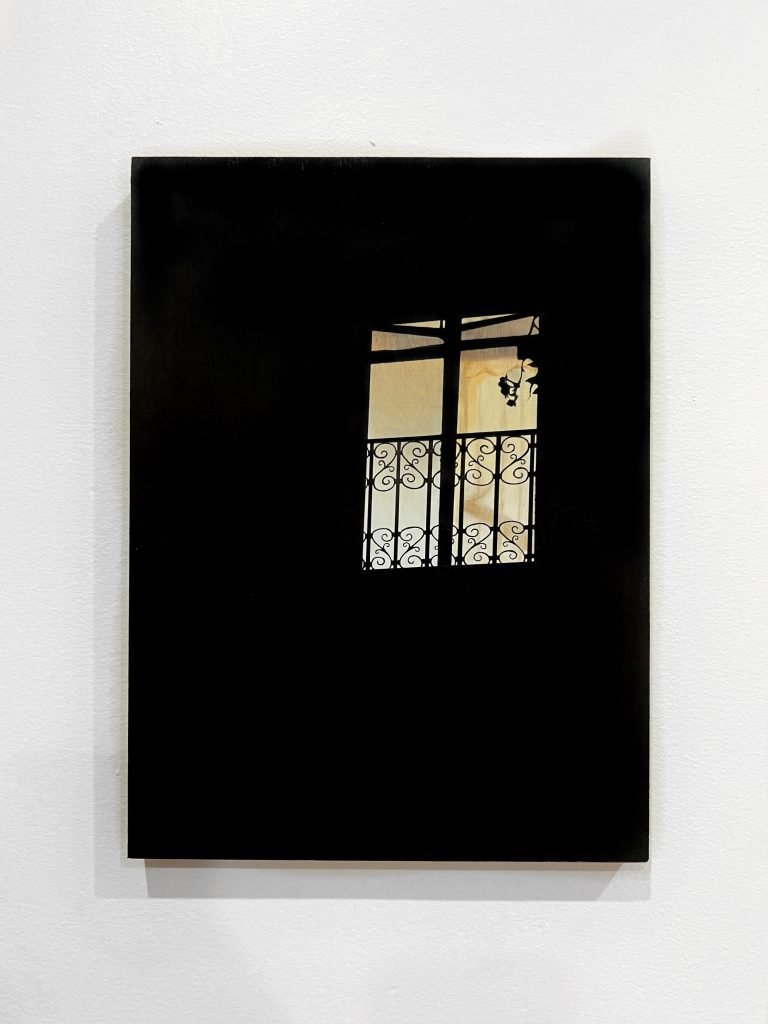

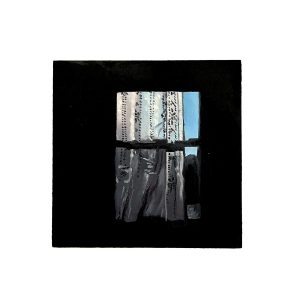

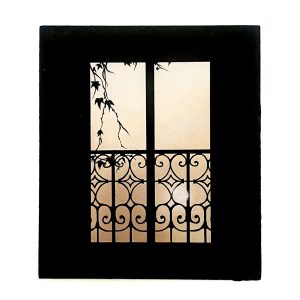

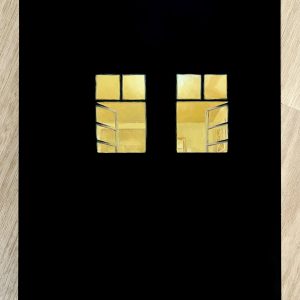

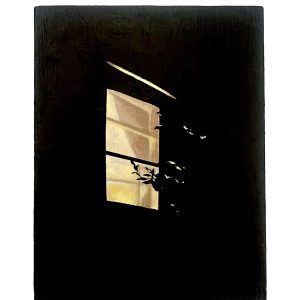

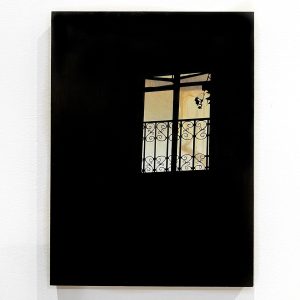

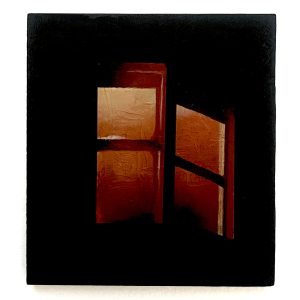

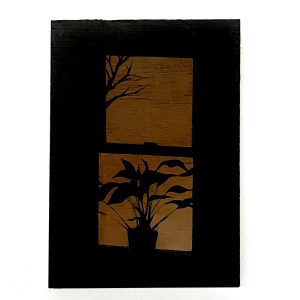

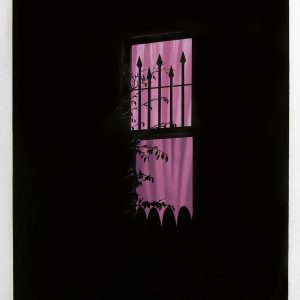

Melancholy lingers within the gallery via the ceramic vessels of Lily Trnovsky, lovingly formed through clay and body. Adorned with verses from iconic poets and clad with weighted chains, her structures bury deep into the soils of despair. Tangled amidst love and death, oscillating between the two in an intense yet silent battle of grief, Trnovsky cries a harmonic siren song to the Romantic era. She interrogates her own notions of grief, yet calmly welcomes it’s inevitability. The presence of her vase-like vessels and functional padlocks invites domesticity into the space, anchored by Chiranjika Grasby’s paintings. Odes to the humble window, she often leaves the audience questioning whether they’re looking in, or looking out. Cold flat blacks provide a grounding void encompassing her glowing portals, spiking out with screens of wrought iron and tree branches. A teetering balance is made between eerie and ordinary, shining light through the darkness of suburban mundanity. And what could be lurking within Grasby’s luminescent spaces? Perhaps the dreams of Inès Cook, which come to life through meticulous autobiographical paintings. She presents recounts of her dreams through props and manufactured scenes, evoking fantasy, storytelling, and romanticism. Cook’s dreamscapes are bizarre and somewhat hallucinatory, yet she reproduces them in compositions that appear ordered and balanced. Her high contrast palettes tells an unsettling tale of firing neurons and inner thoughts swimming through her resting mind.

In its essence, the Romantic spirit comprises an interest in not only what is beautiful and worthy of love, but also the opposing forces that can be sinister and dark. There is an acknowledgement that a world involving only ‘good’ cannot exist, and that a negative must be present as a counterpart. One cannot exist without the other, so they must instead work to keep each other in balance.